Reclaiming Birth from Medical Intervention

From Machines to Mindful Mothers

I’ve grown up with a healthy distrust of authority, particularly within the medical system, throughout my whole life. When I was eight years old, my dad was regularly borrowing books from the library, and I picked up one of his books called The Cancer Cure That Worked by Barry Lynes. The book is all about the work of a man called Royal Raymond Rife, who was born in the late 1800s and did some incredible work around frequencies and cancer.

I devoured this book when I was eight years old, along with some others my dad was reading at the time. Another that had a big impact on my life (which I’ve since shifted my ideology on) was called Why You Don’t Need Meat. So, at the age of eight, I became a vegetarian. And I also concluded that the medical system was not to be trusted.

I maintained that perspective growing up, and I’m very grateful for those early sparks of knowledge that allowed me to do so.

One of the areas I’ve always been particularly interested in is birth. It’s always felt wrong to me that birth takes place in a hospital, looking so clinical and sanitised. Birth became an area I dove into when I wanted to learn about complementary medicine. And it’s something I continue to research. It’s incredibly important to me, as it should be for any woman who wants to birth a child—or any man connected to a woman who does.

Is birth a medical event or a spiritual gateway?

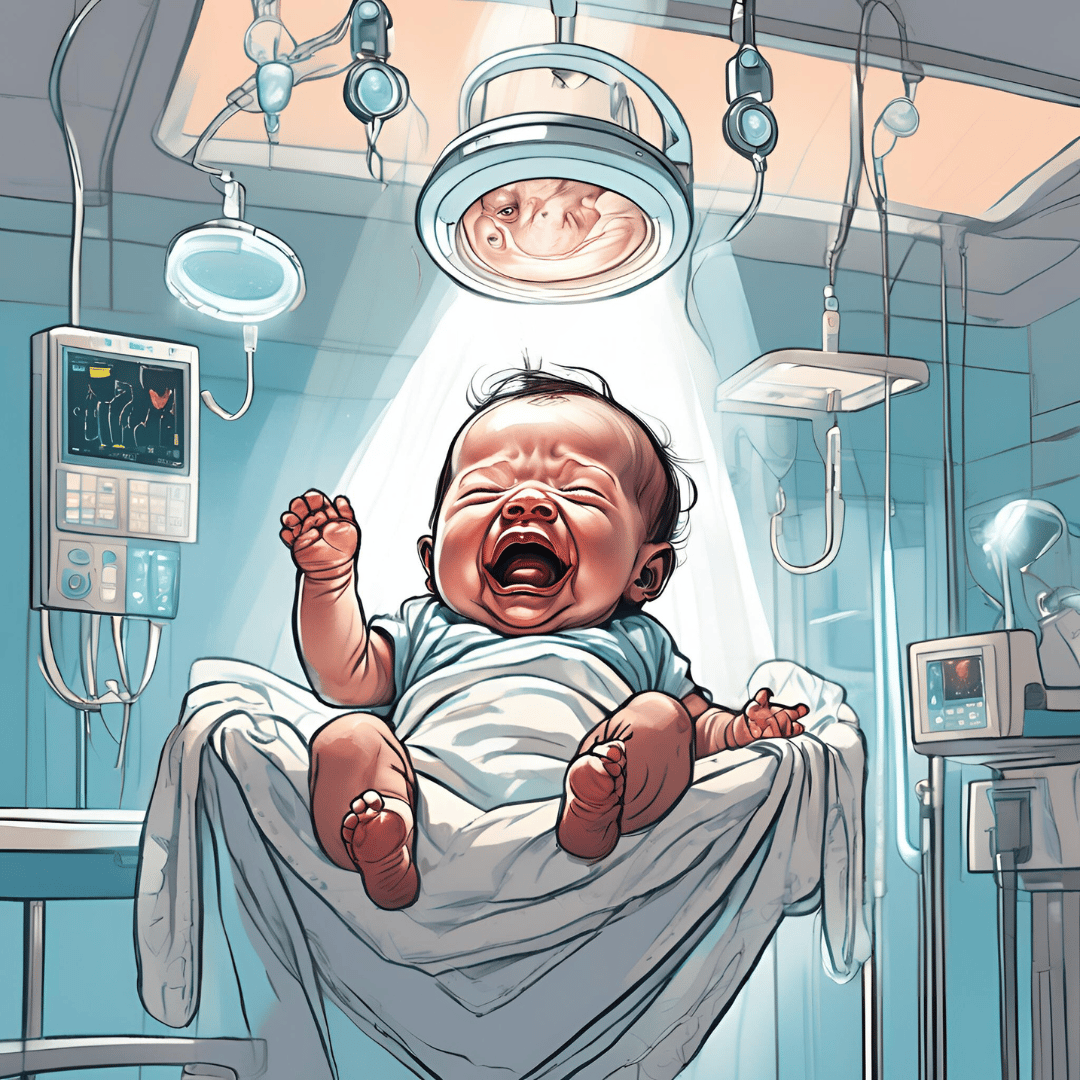

Birth is our first experience of the world, and when it’s medicalised and ritualised, as it so often is today, it’s incredibly damaging. Not only for the mother but also for the children who come into the world in this way through a cascade of interventions by people who, while they may believe they’re doing the right thing, likely know deep down that something about it doesn’t feel right.

These interventions include things like inductions, IV fluids, shaving, enemas, routine foetal monitoring via straps that prevent women from moving freely, rupturing membranes, internal exams, and directing women on how to push. All of this goes against the instincts that come from within a woman. Every woman knows how to give birth; it’s not something we need to be taught.

What’s interesting, as Yolanda Norris-Clark points out in her books, is that "the very reality of believing that we need advocacy during birth is itself a glaring red flag." And it signifies "an underlying awareness that we aren't safe".

We’re told to put together birth plans, and yet most women in communities that have experienced birth—especially in the medical system—talk about how their birth plans weren’t followed. And yes, how do you even plan a birth?

When I birthed my daughter, it took five days, and I certainly didn’t plan for it to take that long—but perhaps she did.

Even though I had a lot of information, it wasn’t information that I truly needed. I needed support. I needed to be trusted. I needed to be gently guided back to my inner compass to understand that I had the power and wasn’t doing anything wrong.

But we’ve been hoodwinked into believing that we don’t trust ourselves the way we should, all because of the programming of the Rockefeller medicine system.

Thankfully, today, we are seeing a dramatic increase in the number of women seeking natural births, saying no to interventions, choosing free birth or home birth, or at least a birthing centre. Many women now hire doulas or midwives to support and advocate for them during birth.

I had planned a home birth. Five days later, I had a natural, medicated birth in a hospital. And what I believe was missing during that time was love, support, and care from other women. I didn’t have a doula; I thought a midwife would be all the support I needed.

But I needed more. Women need other women during birth. That’s why there’s such a movement towards free birth and home birth—because that’s how birth should happen.

It’s considered normal to be given opiates or narcotics for pain relief during birth. But all the natural things that happen while we’re birthing a baby—like feeling nauseous or vomiting—are entirely normal. Yet the medical system tells us they can “fix” them. “We can help you. We can save you. We’ll ‘deliver’ your baby.” They offer ultrasounds, foetal monitors, and all these interventions that are designed to place us—the mothers—into a powerless situation and elevate the doctor to the role of god.

Think about how birth is portrayed in the media and movies. Every time I see a birth on TV or in a film, it makes me scream. The woman is rushed to the hospital to be “saved,” the doctor puts her in a wheelchair, lays her on her back, lifts her legs, and two seconds later, a baby is “delivered” by the doctor.

None of that is reality.

We’re taught that we’re doing it wrong, that maybe our bodies aren’t built for this, and they have to save us.

And yet, we know that birth happens best in an environment where the mother is relaxed. This is what produces oxytocin and all the other hormones and prostaglandins that allow the mother to do what she’s designed to do. She needs calm, she needs darkness, she needs privacy, and she needs to feel safe.

What she needs is the exact opposite of a hospital room.

It’s so strange to me that home birth and free birth aren’t the norm, that cutting the cord before the blood has even fully transferred into the child is considered normal, or that injecting a woman in the leg with oxytocin is standard practice so she can birth her placenta.

We’re only given two hours to push our baby out, and if it takes longer, it’s considered “prolonged.”

Mothers who are 35 years or older when they deliver are considered “geriatric”.

And we just accept this.

Over the years, I’ve heard countless birth stories from women I know and women I don’t. Some are more positive than others.

In 2017, I wrote a story called The Machine of Birth. The inspiration for it came from my study of what birth is, what birth isn’t, and the difference between medicalised, ritualised birth and natural birth.

I was also writing it from the viewpoint of the child—the baby—who is coming into this world for the first time, seeing it all through the lens of their birth.

There’s been a lot of research done on the difference between babies born naturally and those born through intervention and the effect it has on the child.

So, I wrote this story from the perspective of the medicalisation of birth, viewing the woman as a machine who has to do everything in a particular timeframe, in a particular way, without deviation from the plan. Because perhaps the doctors have a golf game tomorrow, or the nurses’ shift is ending soon, or even, as was the case in my birth, another woman may be birthing at the same time, and the midwife may need to leave to support her, prompting a decision to transfer me.

In the story, I also chose to use the term “droids” to describe the doctors and nurses involved in this imaginary birth. The reason for this is that I believe not everyone in the system is fully aware of what they’re doing. They don’t know what they don’t know. They just know the plan. They know what they’ve been trained to do, and they aren’t looking at the full picture. They aren’t considering the energetic, spiritual, physical, and emotional aspects of what it means to birth or be birthed. They’re simply ticking boxes.

This is quite a sobering story, based on everything I’ve learned about birth and how we handle it in the modern world. If you’re pregnant or planning to have children soon, I wouldn’t necessarily recommend listening to this story. But I felt it was important to share, to put this out into the world because this is the norm. This is how most women give birth. And yes, I’ve written it from an extreme perspective, but I’ve done so with intention.

Because as I mentioned earlier, this needs to change.

Interventions are not normal. A woman feeling inadequate is not normal. A woman feeling like she needs to be “saved” is not normal.

I celebrate every time I hear of a woman who has a free birth or brings a new child into the world without needing the medical system. Because every time a woman does this, she shows other women what’s possible—that they, too, are capable of the same.

I love the resurgence we’re seeing in doulas, birth keepers, and midwives helping women find their power and birth the way they were designed to.

So now I’m going to share my story, The Machine of Birth. I’d say, “Enjoy it,” but I don’t think you will from the perspective of what it may bring up inside you.

And at the same time, I’ll ask you to read anyway.

Not if you’re pregnant. If you are, just stop reading. It’s not something you need in your psyche. Instead, go watch a home birth or a free birth of a beautiful baby coming into this world.

My desire in sharing this is simply to have more men and women understand that birth is normal. It's natural. It's celebrated. It's messy. It is the most beautiful thing you'll ever experience.

And yet, most women don't experience it that way. And that's what I stand for. I stand against the ritualisation and the medicalisation of birth. And if you're reading this, it’s likely you do, too.

The Machine of Birth - A Story

The machine has arrived. The droids are busily moving into position. They know what to look for. Their prolonged education has prepared them for this very day. Their eagle eyes are myopic, trained to seek out all that is wrong. They are in control now. Everything will be fine, so long as it doesn’t deviate from the plan. Their carefully laid out plan.

In line with requirements, the machine has been brought in, de-clothed, sanitised, shaven, and has signed away autonomy. Her desires matter no more; her umbilicus is now tied to the hospital that dominates her. All evidence of her individuality is cleansed and washed away by the educated ones.

The droids believe it’s all for the best, not realising their minds are no longer theirs, for they are bound by and tethered to the technocrats they kneel at the feet of.

The machine entered the hospital with a partner, though he was unseen by the droids. His operating system is different, based upon empathy and love, a language they have not yet learned. Emotion was squeezed out of them in training, considered an unmeasurable burden that brings too much baggage. He’s silenced and put in his place. We can’t have him messing with the outcome.

Every stage of the ritual must be manipulated, managed, and timed perfectly; interventions must be only made by the droids at careful intervals, for their eyes are on the prize. The process follows a clear structure and timeline, and the droids all have a place on the assembly line. There can be no deviation from the plan.

It’s the prize, the product that matters most. The machine is a means to the end, an inconvenient obstacle that talks and groans and speaks irrationally throughout the process. The droids are trained to minimise this unnecessary, maddening hysteria.

If the machine attempts to access transcendental realms, she is swiftly crushed. There is no place for otherworldliness in this stark, sterile room.

There will be no spiritual learnings from this birth. The droids come prepared with drugs, machinery, and implements to show the machine her true place in the hierarchy. The machine is not there to make decisions or experience. She is there for the mechanised ritual extraction that brings forth fresh new blood, from which other droids can benefit too.

Since her arrival, the machine has been prodded and poked, tested and touched. They open her and place their hands inside her temple without her consent. There can be no deviation from the plan. They watch the clock and work around her, not with her. All that is in sight is the finish line. All that matters is the arrival of the product.

The journey there is inconsequential. But something’s not right. She is defective. She does not open the way she must. The product is not arriving in the specified time frame.

Perhaps it’s the light that shines so bright, forcing glare into her eyes and making her already weary body tire more. Maybe it’s the discordance of the monitor, interrupting her already fragile consciousness every time it changes pace. Or the tick, tock, tick of the clock?

It could be the droids continually coming and going to poke her and prod her, to ask her questions she’s already answered, and drop hints she’s not quite doing it right. Perhaps it’s because she’s naked and vulnerable, with men governing her as she lays bare.

It might be because she’s thirsty and hungry for food, but the droids deny her sustenance until the prize is delivered. Maybe it would be helpful if she were able to move freely, to use the body given to her for this very purpose, to rise and fall with the surges of power, to walk around the room.

The starkness of the room affects her ability to relax, to surrender, to open her petals like the blooming flower she is. The unyielding noise and ignorant droids prevent her from going within—where she needs to go.

Whatever the reason, the machine knows, through both veiled implication and outright condemnation, she simply isn’t good enough. She can’t provide the product in time. The droids have a schedule, and she must adhere to the timeframe.

There can be no deviation from the plan. The droids take charge. She’s unsure. She tries to speak, but she has no say. She matters not.

More tests, lots of chatter, she doesn’t really know what she’s agreeing to. They don’t need her permission, penetrating her again, tapping into her vein. What little life force she has left soon begins to dissipate. The droids exhale as they pacify her. It is they who know best. The product will be delivered on time. There can be no deviation from the plan.

The symbolic saviours, the lifeline, and the drugs are injected into the bloodstream of the machine, at which point the surges thunderously intensify from rhythmic and bearable to excruciating — in an instant. She bites, thrashes, and squeezes; what she could once handle is a distant memory.

The steady, slowly increasing surges of energy within her womb space, once bearable, now too fast, too shocking. As they flowed through her body with regularity and power, she was able to ride the wave. She now feels like she’ll split open and bleed to death on the bed. Her body writhes in pain, the surges too close and overwhelming. Her natural pain relief is unable to keep up or to quell what has happened so quickly.

The machine starts to spiral; she just can’t take the intensity. The droids cannot wait for her. Their deadline is fast approaching. The machine has already taken enough of their precious time. She is failing; she cannot keep up with the program. She is inadequate and incompetent. They must intervene. Again.

The machine cries desperately for relief. She cannot do it on her own, just as they’d expected. They have been waiting for this moment. She was never strong enough to do this on her own. Only the droids can save her now. They swiftly organise the procedure that will bring much-needed peace to the room.

Another droid arrives to help with the pain. He jabs her in the spine with his vicious, long tool and promises to make it all better. He’ll readily remove the source of the pain, which had appeared so suddenly upon receipt of the drugs, as long as she stops the commotion. He’ll bring her back down to earth where she belongs. To take life from her body to give life to the product.

Focus upon the prize has now intensified — incessant beeping louder and harsher, all eyes on the monitor. Once necessary to some extent, she’s now just a passive machine, vanquished by the militarised process around her.

The sounds, so shrill, take over. She leans back, exhausted, wanting to sleep, to give up. The drugs set in. They are meant to save her, but the feelings shift from pain to powerlessness — what little she had now crushed. She is just a byproduct. All she wants to do is rest. Her hopes are dashed, her spirit torn.

She wonders if it’s meant to be like this. Why are the droids so harsh? Why has she been reduced to a hysterical vessel that houses a prize more valuable than she?

Her lover is lost, too. His deep desire to hold and protect her is at odds with his belief the droids know what’s best for her. It doesn’t seem as if they do, but they assure him they have it all under control. What is he to do? There are more of them than he. He’s outnumbered, untrained, unprepared. His love is forever in her keep.

Each time the droids touch her, he rages inside. She is hurting; his hands are tied. He wants to envelop her and smoothly guide her through the gateway she is so adequately designed to cross. To share in the magic with her on the other side. But his dreams are rudely shattered when the beeping starts to quicken. The product is under duress.

Perhaps he picks up on his mother’s fears, as the cycle of intervention reinforces her paralysis and lack of faith in what her body is designed for. Perhaps he picks up on his father’s fears and intense desire to help his lover navigate this journey.

Maybe it’s confusion as the natural and synthetic hormones cascade, too much oxytocin coursing through their veins. It could be all the noise and commotion, the frenetic pace of the room. Or the sudden fogginess and dizziness he feels, the disconnection from his once-bonded mother. The path once lit is now dark and unknown. He, too, begins to spiral out of control. His heart racing, his future now uncertain.

His safe existence within a serene and restful world — no longer. Would he ever enter the magical world in his dream? A world as soothing, loving, and nurturing as where he’d come from. A place he’d transition to slowly, with care, where he’d learn to breathe in a different way and expand upon the already beautiful bond he’d forged with his mother, the machine.

But now his hopes are dashed. There can be no deviation from the plan.

He’d been violently torn from his mother. It was stark, cold, and mechanised, just the way the droids liked it to be: predictable. He doesn’t remember much except panic and pain. He tried so hard to make it against all the odds. He was on the home stretch and could see the finish line.

He could no longer feel the connection to his mother. Something was wrong. He, too, wasn’t good enough for the robots. It all became cold and loud, and with a rush came a fierce pull at his feet. He wasn’t expecting it to be like this.

After being removed from his warm home, it all happened so fast. It was so intensely bright. He was rubbed and weighed, then blinded and jabbed in his leg. He gagged on metal as he was suctioned and forced to learn to breathe. His first breath was a cry.

He cried for his home and all he’d ever known. He so desperately yearned to return to the place that would soothe him as he tossed and turned. Of nourishment and softness — but there was none of that here. Instead, he met the droids, so gleefully in control.

A place where his mother was treated like no being should be. A new mother, who so bravely entered the portal, not knowing what she would find.

All she found was what never should be.

This moment in time was so bittersweet. A remarkable gift had arrived, and yet this brave mother could not understand the sadness when she wandered in her dreams. She and her son could both not help but feel incapable.

The question is unanswered. Is this how it’s meant to be?

At last and at least, her son had arrived, the most beautiful boy she’d ever seen. In her drugged stupor, she could not feel fully the magnitude of the events that had unfolded. And so she said to the droids, much like a machine: “Thank you for saving my baby.”

With love,

Aimee

x